I can’t forget the first African violet I ever propagated from a single leaf. It sat quietly on a shelf, doing nothing for weeks, and I was convinced I had failed.

Then one morning, while watering nearby plants, I noticed tiny green bumps pushing through the soil. That moment changed how I saw indoor gardening.

African violet propagation is not flashy or fast. It is slow, forgiving, and surprisingly emotional, because it teaches patience in the gentlest way.

This guide walks you through the entire process in detail, not as instructions on a label, but as a lived experience you can follow from start to bloom.

Why African Violets Are Perfect for Leaf Propagation

African violets are uniquely generous plants. Each healthy leaf stores enough energy to produce roots, crowns, and eventually flowers.

Inside the stem are dormant cells waiting for moisture, warmth, and time. When those conditions align, the plant responds by rebuilding itself from scratch.

What makes this process special is reliability. Unlike many houseplants that root inconsistently, African violets propagate with remarkable predictability when treated gently.

The new plants are exact genetic copies of the parent, meaning leaf shape and flower color stay true.

That is why collectors love this method and why beginners succeed so often with it.

The Importance of Choosing the Right Leaf

Everything begins with leaf selection, so I never rush this step.

The leaf should come from the middle row of the plant, not the tiny new leaves at the crown and not the older, fading ones at the base. Middle leaves strike the perfect balance between youth and stored strength.

A good leaf feels firm when touched, with even coloration and no tears, spots, or limp edges.

If the leaf already looks tired, it will struggle to support new growth. When I choose carefully, I notice the entire process unfolds more smoothly later.

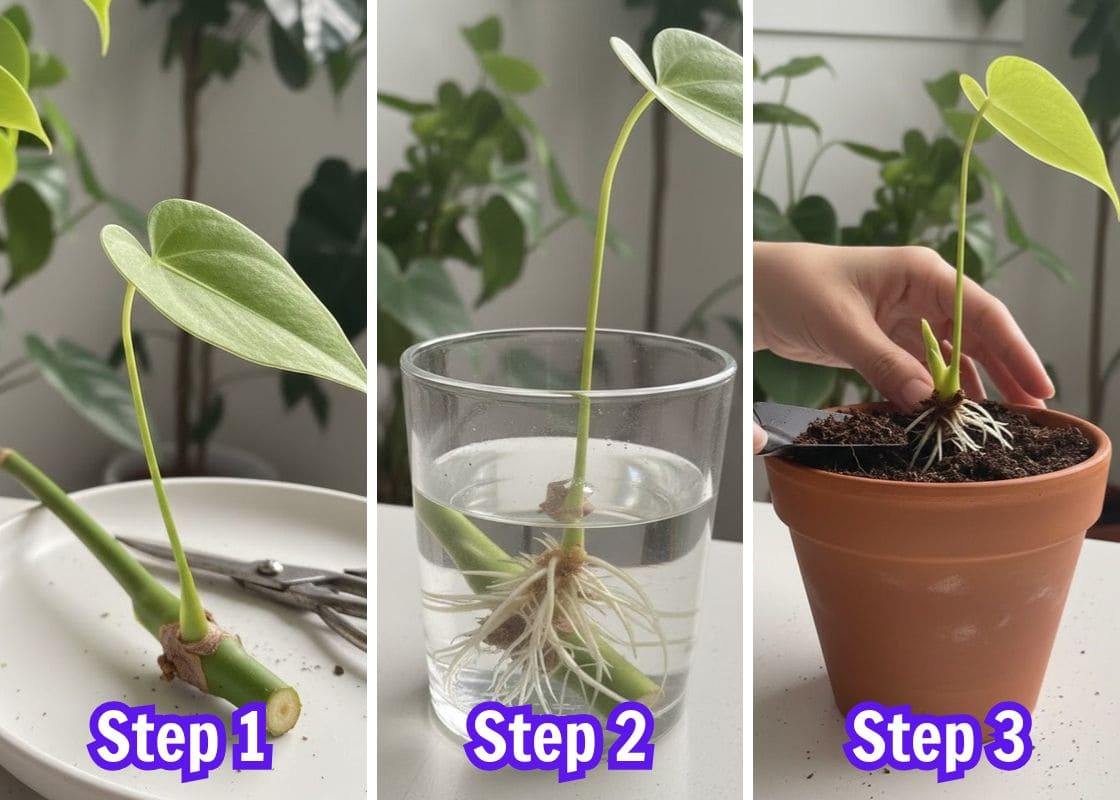

Preparing the Leaf With Care

Once selected, the leaf needs a clean, deliberate cut. I use sharp scissors or a razor blade cleaned with alcohol.

The stem gets trimmed at a forty-five degree angle, leaving about one to one and a half inches attached to the leaf.

This angled cut increases the surface area where roots will form and reduces the chance of rot.

Note: A rough cut traps moisture unevenly and invites decay. A clean cut heals faster and signals the plant to begin rooting.

Planting the Leaf and Setting the Foundation

I prefer soil propagation because it allows the roots to form naturally in their final environment.

The soil mix must be light and airy. Heavy potting soil holds too much water and suffocates young roots. A blend of peat or coco coir with perlite creates the right balance of moisture and oxygen.

When planting, only the stem goes into the soil. The leaf blade stays fully above the surface. I gently firm the soil around the stem so the leaf stands upright without support.

If the leaf leans or sinks, it usually means the soil is too loose or the stem too short.

At this stage, restraint becomes essential. The soil should feel lightly moist, not wet.

Overwatering is the most common mistake I see, and it often leads to silent failure beneath the surface.

Creating the Right Environment for Growth

African violet leaves root best in stable, humid conditions.

I cover the pot with a clear plastic cup or loosely tent it with a plastic bag. This creates a miniature greenhouse that slows moisture loss and reduces stress on the leaf.

Light should be bright but indirect. I avoid sunny windows and choose locations with filtered light or a few feet back from a window.

Temperature consistency matters more than warmth. Around twenty-one to twenty-four degrees Celsius is ideal, with no cold drafts or sudden heat spikes.

Once the leaf is placed, I resist the urge to move it. Stability builds confidence in the plant.

The Long Wait and Subtle Signs of Success

For the first few weeks, nothing seems to happen. This is where many people give up too early. Beneath the soil, roots are forming quietly.

Around week three or four, the leaf feels more firmly anchored when touched gently. That resistance is the first sign of success.

Between weeks six and ten, tiny plantlets begin emerging near the base of the stem. They look fragile and impossibly small, but each one holds the future of a full plant.

Watching them appear feels deeply satisfying, because the progress is earned, not rushed.

Separating the Baby Plants

Once the plantlets develop several small leaves of their own, they are ready to live independently.

I carefully remove the soil and separate them by hand, moving slowly to protect the roots. Each baby gets its own small pot with fresh soil.

This transition period matters. I keep the light gentle, water sparingly, and avoid fertilizer until the plants establish themselves.

Within a few weeks, they begin to grow confidently, no longer relying on the original leaf.

Common Problems and How I Avoid Them

Most failures come from excess moisture, poor airflow, or impatience. Soggy soil suffocates roots, direct sun scorches leaves, and frequent checking disturbs fragile growth.

I remind myself that African violets prefer calm conditions and steady routines.

When something goes wrong, it is usually a signal to simplify rather than intervene.

The Reward: Blooms That Feel Personal

Within six to nine months, most propagated African violets bloom. Seeing flowers on a plant you grew from a single leaf feels different than buying a flowering plant from a store.

Refer to: All You Need to Know About The Secrets to Make African Violets Bloom Abundantly